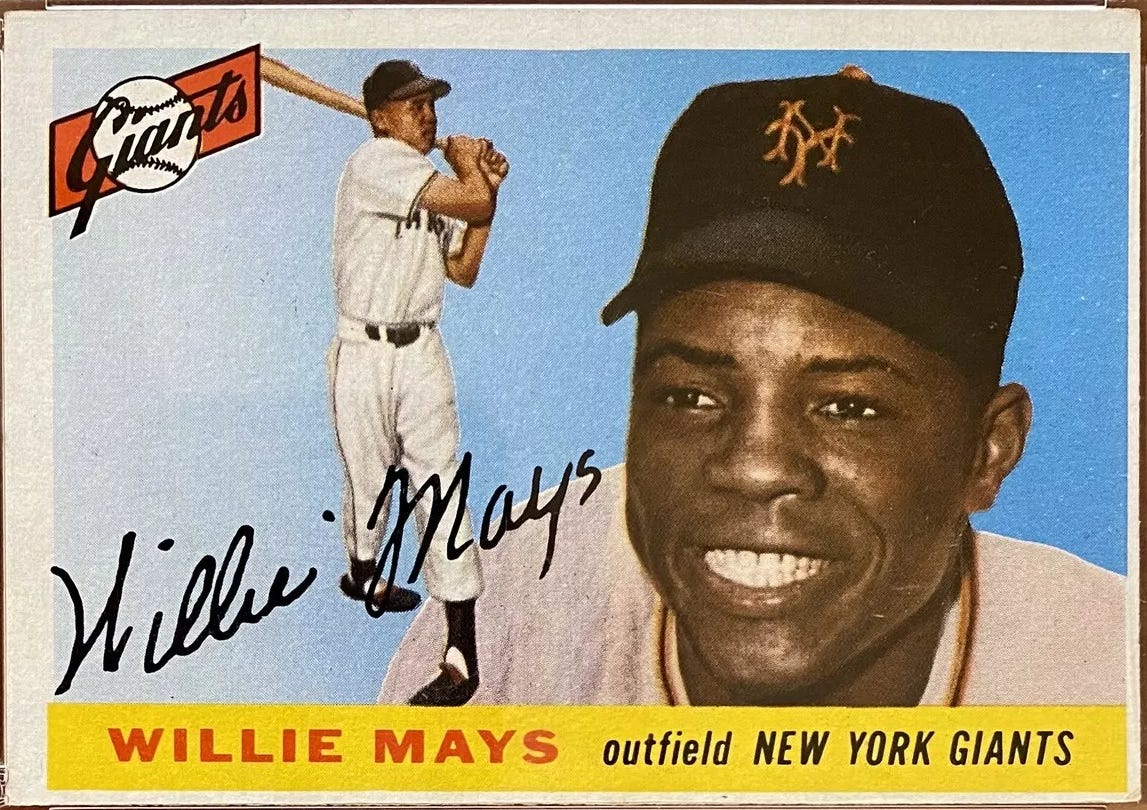

Willie Mays Was Baseball’s Greatest All-Around Star

The sport lost one of its all-time greatest heroes, on and off the field, on Tuesday.

The most famous moment of Willie Mays’ career came relatively early on. In Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, the then-23-year-old New York Giant was patrolling the cavernous center field of the Polo Grounds, where the outfield wall was 483 feet from home plate. When Cleveland Indians first baseman Vic Wertz smashed a fly ball over the head of a shallow-playing Mays with two on and none out in the eighth inning of a tie ballgame, it seemed like a bases-clearing triple or even an inside-the-park home run was about to happen. The idea of an out? Impossible. That is, until Mays pulled out a miracle:

We don’t have fancy Statcast metrics for Mays’ era, but the great YouTuber Foolish Baseball did a deep dive estimating them a few years ago, and he struggled to find any truly comparable examples of modern players covering the ground Mays did (115 feet) in the time he did it (5.7 seconds) while making the throw he did back into the infield to keep any runners from scoring. It was arguably the signature defensive play in baseball history.

We’ll be thinking a lot about these kinds of memories over the coming days, as tributes come flooding in about the life and career of Mays, who died on Tuesday at the age of 93. Mays was nothing less than a larger-than-life figure in the game of baseball: Only he could pull off the GOAT play as a fielder while also hitting 660 career home runs — sixth-most all-time — and stealing 339 bases, among his long list of records and accomplishments. It’s part of why Mays has a strong case as the most well-rounded player in MLB history: because his game had no weaknesses.

We can see this all-around greatness in a few ways. The first is if we look at Mays’ value added across different phases of the game. Yes, he is a Top-3 career player no matter which version of Wins Above Replacement you look at — trailing only Babe Ruth and Barry Bonds — but Mays did it in a more complete way than any other player. Using my JEFFBAGWELL metric, which averages together both versions of WAR, we can also break out how many runs above average1 Mays added as a batter, a fielder (including positional value) and a baserunner. If we take the geometric mean of each value,2 here are the most versatile WAR players in history:

Mays also epitomized the classic “five-tool” player: Somebody who could hit for average and power, run with speed, play excellent defense and throw with a cannon for an arm. We don’t really have a way to measure Mays’ arm strength in the pre-statcast era — though, again, that 1954 throw probably covered at least 300 feet to get back into the infield at the Polo Grounds, which stands up with other throws on this list.

But even if we have to toss out the arm factor, Mays is the best “four-tool” player in baseball history (minimum 3,000 plate appearances) if we take the geometric mean of FanGraphs’ various “plus” stats — which are scaled such that league average is always 100 — over each player’s career:3

Beyond the wide array of skills on the field, Mays was one of baseball’s greatest ambassadors, embodying the grace and class of an icon. He was the Giants, even as they moved from New York to San Francisco, and even long into his retirement. But he also served as a living legend for so many decades, representing a link back to the golden age of baseball in the middle of the 20th century, when the sport truly was America’s pastime.

Because of that, the magnitude of Mays’ loss is immeasurable, no matter how much we can quantify about his performance on the field. Out of the nearly 23,000 players who’ve put on the uniform in major league history, it’s fair to say that nobody played the game how it was supposed to be played quite like the “Say Hey Kid” did.

Filed under: Baseball

Prorating shorter seasons to 162 team games each year.

Since the scales of what are good batting, running and fielding run totals are different from each other, we want to keep larger numbers from overwhelming the average.

For speed, I used Bill James’ Speed Score relative to league average; for defense, I used FanGraphs’ defensive runs per 600 plate appearances, with the 20.5 runs of replacement value added back in as well.

Well done. An incredibly sad day, but what a legacy. Even today, it's hard to believe just how good he was. It's why statistical work by you and others help preserve a deep respect for the past as memories grow hazy and eventually fade away and disappear.

Even more incredible to me, is that after the 1973 World Series (I am a longtime A's fan), it became common to here people say that Mays was "overrated," a "showboat," and "hurt his legacy" with his performance in the Series. Some of that came from Yankees fans in the New York press. Still, even as a young kid rooting for Oakland that struck me as unbelievably ridiculous and cruel.

What I saw over time, however, was that none of that appeared to matter to Mays. He, as you say, embodied "the grace and class of an icon." Despite his staggering accomplishments as a player with the clear right to defend himself, he elected instead to carry himself with class and a quiet dignity in a way that vanquished his naysayers and critics.

It's a sobering reminder that legacies should not be assessed with "hot takes" or G.O.A.T. proclamations but allowed to mature and marinate in the minds of the interested community over time. Mays will forever be missed but will continue to inspire awe in anyone who decides to pick up a glove or review his career.