Which Sports Provide the Best Return on Your Time Investment?

And if we can’t shorten regulation games, can we at least shorten overtimes?

Recently, Adam Silver caught a lot of flak for telling Dan Patrick has was “a fan of four 10-minute quarters” in NBA games. And I get it. Although I tweeted noted at the time that we should hear him out — if not simply because shorter games might be a clever way to help alleviate some of the league’s structural problems — I also recognize that it would profoundly alter many fundamental things about basketball and its record book, while not even necessarily accomplishing what it might be intended to accomplish.

And it might also be a solution in need of a problem, in some ways.

Are NBA games too long? Put aside whether 82 of them are too many in a season — that fact is fairly undeniable. But the overall economy of action within a basketball game consistently rates among the best of any sport, something we can track in a number of different ways.

The first — and simplest — way would be to look at the ratio of real-life time it takes to watch the average game by sport to the purported amount of time the game takes in terms of the scoreboard clock. (Excluding baseball, because it famously doesn’t have a clock.)1

By this accounting, football has the greatest amount of “false advertising” in terms of how much time the game actually takes versus how long it lasts on the clock. Hockey, by contrast, is the most honest — with a ratio of 2.5 “real” minutes per minute on the scoreboard — with NBA games checking in right behind at 2.8 “real” minutes per clock minute.

Don’t get me wrong: That’s still kind of a crazy ratio, a testament to how packed each game has become with non-action such as advertising or stoppages for things like replays, challenges and the like. Very few of the features causing such bloat in the modern versions of these games existed when the sports were originally invented.

Which brings us to another way of looking at the problem: How about the amount of action within a game itself? Back in December,

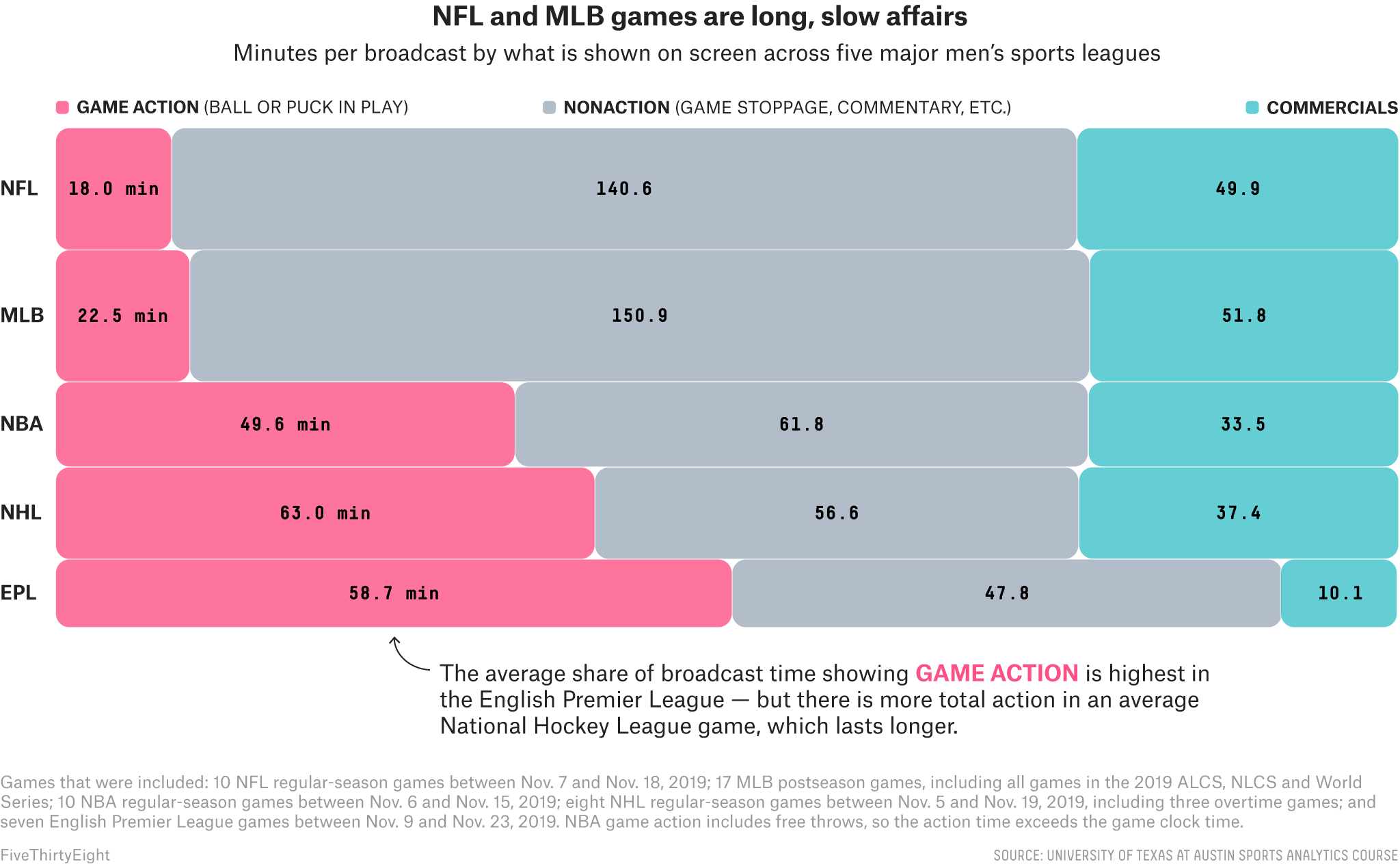

did a great job breaking down the amount of live action versus breaks in play for various different sports — here were his findings:(Credit: )

According to his research, basketball games had the second-highest ratio of live action to non-action, with 69 percent of total broadcast time featuring the actual game itself. They only trailed soccer, which is its own animal in these regards (we’ll get to that in a moment). And again, football — both college and pro — featured the most bloat, in terms of non-action versus action ratio. In a roughly 3 hour and 20 minute football game, more than an hour of that was spent on commercials, intermissions or other breaks.

Of course, there are other, adjacent ways to track this phenomenon — such as this research by Kirk Goldsberry and Katherine Rowe from a few years back at FiveThirtyEight:

(Credit: FiveThirtyEight)

They tracked things at a more granular level, recording actual breaks between literal live-ball (or puck) situations even while the broadcast was rolling. I think I favor Stephan’s method better, because sometimes the breaks in between “live play” are kind of the point, too — the tension that builds between pitches in an MLB playoff game or between plays in a critical NFL 2-minute drive is actually the essence of how those sports create drama — but again, the NBA comes out in the same class as hockey among the non-soccer sports in terms of giving you bang for your watching buck with actual action.

The big flaw of basketball is the endgame, when a procession of fouls and free throws often ruins what had been an enjoyable flow of gameplay for the previous 46+ minutes. In this fascinating post from about a decade ago, Mike Beuoy of Inpredictable found that the final 2 minutes of a close NBA game took about 12 minutes of real-life time to complete, and that the final minute took up as many as 9 minutes of real-life time. Here’s his incredible chart of ratios between real-life time and clock time remaining in regulation, based on the score of the game:

(Credit: Inpredictable)

The NBA has experimented with fixes for this, such as the Elam Ending in the All-Star Game and G League — and while that would also be a jarring departure from history and perhaps have unforeseen consequences on records, it would probably be a less radical change than 10-minute quarters while also improving one of the most glaring flaws in the watchability of the game.

One other, even easier area where basketball — and other sports — might make games shorter without huge side effects is in overtime. The NBA’s current 5-minute OT structure adds on more than 10 percent of a regulation game for just one extra period, while the WNBA and college basketball tack about 13 percent of a new game onto the end of a tie game after regulation.

Here’s how different sports’ OT lengths compare as a share of a normal regulation game (excluding college football, which can also get absurd with OT but doesn’t really have a timed clock in the extra periods):

The NFL, which only recently reduced its OT from 15 minutes — or 25 percent of a new regulation game — to 10 minutes, holds the crown here as well in terms of adding too much extra time relative to other sports. (Though it should be noted that the practical amount of time these overtimes last is less than the full 10 minutes, as only about 8 percent of OT games have ended in ties since the length of overtime was changed.) And the NHL is once again the most economical, with 5 minutes of OT only representing 8 percent of a new regulation game — shootouts notwithstanding.2

The NBA could join the NHL’s ratio by shrinking OT to 4 minutes, which would also be an application of Silver’s 10-minute quarter logic (but for situations that only come up about 6 percent of the time). Hell, 3 minutes is probably enough — it would provide about 6 possessions per team at the league average rate of pace factor, which seems like plenty to determine the deserving winner.

And in general, I think every sport should probably consider dropping its OT length below that 10 percent ratio versus a regulation game. We shouldn’t be adding 10-20 percent of an entirely new game at the end of an existing one just to break ties, especially in the regular season.

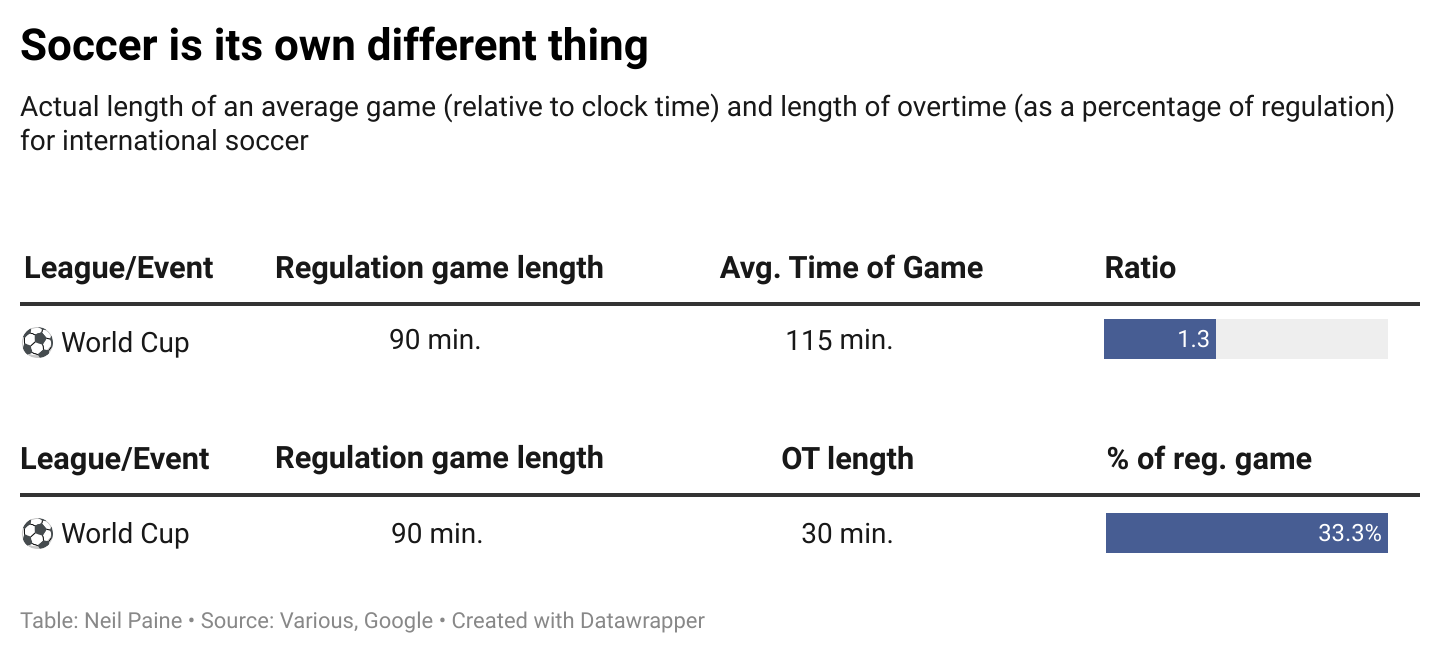

Now, I mentioned soccer as kind of its own thing earlier. Its ratio of real-life time to clock time is, famously, far closer to 1:1 than any of the North American sports (especially those “other” footballs). For instance, if we account for 90 minutes of regulation play, 15-minute halftimes and an average of 10 minutes of added time for stoppages, the ratio of real time to clock time at the 2022 World Cup was 1.3, far less false advertising in game length than any of the sports we listed above:

The flip-side for soccer, however, is its mandatory overtime featuring two periods of 15 minutes each, which applies in the World Cup as well as domestic leagues such as MLS. Having 30 minutes of OT represents 33 percent of an entirely new game, which is far out of line with any of the other leagues previously listed. Soccer giveth economy of time, soccer taketh away.

So, anyway, is Adam Silver right that NBA games should be shorter? Maybe in some ways — mainly for the purposes of competitive balance and possibly to discourage load management. But four 10-minute quarters feels like a drastic overcorrection to a problem that isn’t all that pressing, in terms of pure watchability. Basketball already provides one of the best action-to-dead-time ratios of any major sport, and most of its bloat comes in very specific areas, such as endgame fouling and overly long overtimes. Fix those first, and then maybe we can talk about lopping 8 minutes off of regulation games.

Filed under: Insane Ideas, Frivolities

Unless you count the new pitch clock.

And similar to the NFL with walk-off scores, the odds of a goal coming early in NHL OT is higher than we might think.

A related analytics project might be in which sports is it worth the most to watch the beginning. A methodology could be to use the closing moneyline as a proxy for initial win probability and compare the halftime win probability (a bigger difference would suggest more value in watching the first half).

I loved the Elam Ending All Star Games. I do love a good buzzer beater, but removing any incentive to foul takes precedence for me. Start with three 10-minute periods, then take the average score of the losing team from those periods and add it to the leading team's score for the Target. Make it happen Neil!