Team Timelines: How the Oakland A's Played Moneyball

A look at the different franchise eras that led up to the season immortalized by book and film — and the moves that made it all possible.

Welcome back to Team Timelines, a series that I (very) periodically do here on the ol’ Substack. If you’re new to the series, the idea is to break down how a particular iconic team came into being by looking at the distinct roster eras that led up to it, or out of it, and which players came and went along the way.

The subject this installment? The Moneyball-era Oakland Athletics.

What other teams do you want to see a Timeline for? Let me know in the comments below, or in a note or DM.

Just by virtue of what this series is, most of the teams we will be covering here are champions. Often those are the most interesting squads to map out the long-term team-building arcs of — or at least, the most satisfying ones. Everyone loves a happy ending. But in this case, we’ll be talking about a team that famously never made a World Series, or even won an ALCS game, much less won a title. Their boss famously once said, “My shit doesn't work in the playoffs.”

And yet, the Oakland A’s of the early-to-mid 2000s are among the most influential teams in baseball history, at least in the modern age. A bestselling book was written about them by Michael Lewis, which in turn became an Oscar-nominated movie. That story inspired countless people — myself included — to pursue careers in sports analytics, a movement that would subsequently change sports forever for good and for bad. Nowadays, every front office in baseball (and most in sports other than baseball, too) has more in common with the 2002 Oakland A’s brain trust than with the typical management team that came before it.

So how did the Moneyball A’s come to be? Where did this story start — and how did Oakland build up to the peak of the Moneyball revolution before tearing it all down again (and again)?

The Eras, 1997-2011

As usual, I’ll be working backward from when the first player on our team of interest — targeting the book-worthy 2002 Athletics — joined the franchise,1 and tracking how often the team turned over its roster (losing the majority of its original production)2 at different points along the way. Oakland cycled through more than half its players twice en route to building the 2002 version of the club, then did it three more times as the franchise tried to retool and ultimately rebuild into an entirely new ballclub on the other side:

Our story begins in 1997, with the Oakland debut of SS Miguel Tejada — the first member of the 2002 A’s to join the club and stay with it continuously — and what happened to also be the team’s last season under longtime general manager Sandy Alderson before he turned the reins over to his protégé, a failed former A’s prospect turned scout and assistant GM named Billy Beane.

Part 1: Beane takes control (1997-1998)

The team Beane inherited from Alderson (who had been GM since 1981) was in a period of deep transition. Not too long before, Oakland had gone to three consecutive World Series in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, and it even boasted the top payroll in MLB in 1991 with a list of stars that included Rickey Henderson, Mark McGwire, Jose Canseco, Dennis Eckersley, Dave Stewart, Dave Henderson, Bob Welch and more. But after owner Walter A. Haas Jr.3 died in 1995, the A’s started shedding payroll and star power, falling in 1997 to their worst winning percentage since the miserable 1979 campaign.

And while Beane quickly got to work improving the 1998 A’s, gaining 9 wins in the standings by adding productive veterans like Kenny Rogers (or re-adding in the case of Rickey Henderson) and emphasizing plate patience, this period was mostly a bridge to a younger and more cost-effective version of the team. The new A’s would rely more on their Top-5 farm system, one which had already yielded the likes of Tejada, 3B Eric Chavez and RF Ben Grieve, who won AL Rookie of the Year in 1998. Otherwise, most of the A’s from this early Beane era were filtered in and out quickly.

Part 2: Rise of Moneyball (1999-2001)

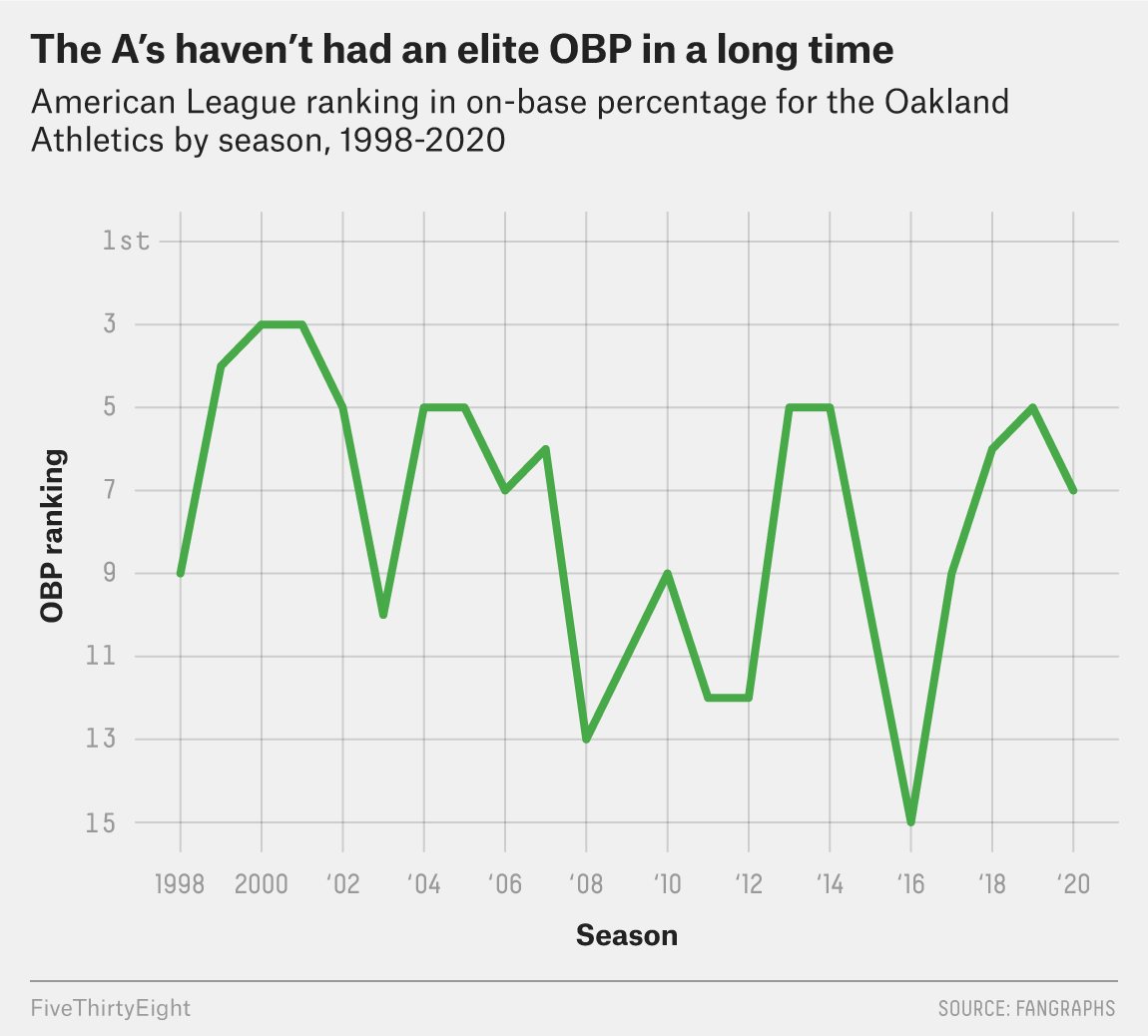

The 1999 season was when the major hallmarks of Moneyball, as highlighted by Lewis’ book, truly came into focus. En route to winning 87 games, their most in seven years — ending a stretch of six straight losing seasons — the ‘99 A’s led MLB in home run differential and were second in walk differential, the classic Earl Weaver-style “walk, single and 3-run homer” offense that also turned out to be sabermetrically approved. Then the 2000 and 2001 A’s raised the bar even higher, ranking third in scoring each year (behind Top-6 on-base percentages) as 1B Jason Giambi rose to MVP status.

Defense was not necessarily a huge focus for these teams, as evidenced by the presence of so many Matt Stairs and John Jaha types. (Even Grieve was a huge defensive liability, which is partly why he never lived up to the promise of that RoY campaign.) But a rapidly improving pitching staff — more on them later — was good enough to help lead Oakland back to the playoffs in 2000 for the first time since 1992.

Once there, of course, they would suffer a crushing defeat in a do-or-die contest, setting up a theme that would be revisited over and over in the Moneyball age. The 2001 postseason offered more of the same; what the Yankees call “Jeter’s flip” will forever be “Jeremy Giambi’s non-slide” to the A’s. And then, New York added insult to injury by luring Jason Giambi into pinstripes via free agency following the season, to go with the loss of OF Johnny Damon to Boston. As quickly as Beane had remade the A’s into a 100+ win contender, he’d churned through more than half the contributors on that team as well.

Part 3: Oakland goes Hollywood (2002-2004)

This is where the story of Moneyball picks up, with Beane contemplating how to cover for the losses of Giambi and Damon in the offseason of 2001-02. And while Lewis’ book always emphasized how the underdog Athletics’ lineup survived through the power of OBP — leaning into underpriced on-base machines like Scott Hatteberg and David Justice — the truth was that this formula was already beginning to pass Oakland by during the 2002 season and beyond. Here’s a reprint of a chart I made back at FiveThirtyEight:

If the market was catching up to Beane’s statistics on the offensive front, however, it still had no answers for the oldest weapon in the sport: an elite starting rotation. It was no accident that three of the four most valuable players on the A’s of this era by Win Shares — Tim Hudson, Barry Zito and Mark Mulder — were ace starters who made sure Oakland ranked no worse than No. 9 in rotation WAR in any season they were together (and Top-3 four times in five seasons) from 2000-04. Yet, it remains confounding how little of Hudson/Zito/Mulder we get in Moneyball; here’s what I wrote on that subject back in 2020:

[T]he OBP-centric narrative of “Moneyball” obscured just how great Beane was at drafting, developing or otherwise uncovering great pitchers. Early on, the A’s were far more driven by high-quality pitching than you might have known from reading Lewis’s book: From 2000 to 2003, Oakland had the third-most pitching WAR in MLB (compared with the ninth-most WAR from its position players). Those A’s were led by three of the 13 best pitchers in baseball according to WAR — Tim Hudson (fifth), Barry Zito (ninth) and Mark Mulder (13th) — a trio of aces who were mentioned a grand total of 32 times4 in “Moneyball.” (For comparison’s sake, Scott Hatteberg, who was worth only 7 percent as many WAR as the Zito-Hudson-Mulder trio, was mentioned 121 times.)

Perhaps the story of three incredible starters doing a lot of Oakland’s heavy lifting would have obscured the juicier A’s narrative of winning through math — particularly since the not-so-analytical Atlanta Braves of the same era had that same formula. Either way, the ‘02 A’s were a great story, and Lewis was exactly the right author at exactly the right moment to capture a team that was, however briefly, touched by the baseball gods:

Again, the magic of that season came to a crashing halt in the postseason against the Minnesota Twins, who in an alternate universe could have been the subject of Moneyball instead. (They went further in the playoffs that year on basically the same shoestring budget.) Reloading with much the same core5 for 2003, Oakland earned a fourth straight playoff berth… and then lost yet another do-or-die elimination game, this time to the Red Sox after blowing a 2-0 series lead in the ALDS. After losing Tejada to Baltimore and Ramon Hernandez to San Diego for 2004 — out of all the stars he could have kept, Beane somewhat infamously chose Chavez for a big extension instead — the A’s broke 90 wins again, but it wasn’t enough for the playoffs. Then, it was time to churn once more.

Part 4: Re-tooling (2005-2007)

It’s remarkable how quickly the iconic Moneyball team was replaced by mostly new names and new faces in those gorgeous Oakland uniforms. A strong believer in Branch Rickey’s old edict, “better to trade a player a year too early than a year too late,” Beane would deal many of his biggest names before they got too expensive or robbed him of his roster flexibility — which led him to deal both Mulder and Hudson within a span of days in December 2004, adding to an exodus that also included OF Jermaine Dye and RP Chad Bradford, a main character from Lewis’ book.

Unlike many small-market, low-payroll teams who have to break up their golden generation and rebuild again from scratch, however, Beane and the A’s expected to keep contending through the upheaval. A new rotation of Zito + Dan Haren + Joe Blanton + Rich Harden, with Huston Street closing games, had arguably as much raw talent as its predecessors did. Chavez anchored a lineup with plenty of promise as well. The Moneyball dream of outracing the market to undervalued wins was alive and well through this new iteration of the club — especially in 2006, when (somehow) a team led in part by Nick Swisher, Jason Kendall, a 38-year-old Frank Thomas, Mark Ellis and Milton Bradley won more playoff games in a season than Giambi, Tejada, Hudson or Mulder ever did in A’s uniforms.

That run came up short in the ALCS, however, against the Tigers, who unceremoniously swept Oakland to end their season. Zito would head to San Francisco after the season, with a handful of other regulars also moving on to new teams. Little did they know in the moment, but it was the last time any version of the A’s with ties to the original 2002 Moneyball team (aside from Beane) would appear in the playoffs.

Part 5: The end? (2008-2011)

After missing the playoffs in 2007 with their first losing season in nearly a decade, Beane engaged in one more churn, replacing more than half the Win Shares from the 2005 team by 2008. Among members of the ‘02 team, only Chavez and Ellis remained through this era, and even the promising, young post-Moneyball 2005 core was mostly either gone or on its way out.

But if a new youth movement was underway in Oakland, Beane was also hitting the point of diminishing returns — this group of prospects simply didn’t have the star power that its precursors did. As the losing seasons piled up, the franchise felt increasingly adrift, with Beane cycling through strategies (Speed? Defense? Pitching again?) in search of a return to glory that never quite came.

After Chavez’s time in Oakland fizzled into sub-replacement level irrelevance, the A’s traded Ellis to Colorado on June 30, 2011, thus sending away the last vestige of Moneyball once and for all.

The Aftermath

For most teams, and most GMs, this would be where the story ends. A remarkable run for a low-payroll upstart has a spectacular peak, manages to iterate a few additional times for more successful seasons, and finally runs out of fuel before resetting for a long time.

But maybe the most amazing thing about Beane’s A’s is that they would pick right up with 94 wins and a playoff berth in 2012, behind an entirely new group featuring the likes of Josh Donaldson, Josh Reddick, Yoenis Céspedes, Coco Crisp, Bartolo Colón and others. And when that group found itself scattered in the mid-2010s, Oakland built yet another winning team around the likes of Marcus Semien, Matt Chapman, Matt Olson, Mark Canha, Jed Lowrie and Sean Murphy. Incredibly, Oakland made just as many playoff appearances in the 2010s as it did during the 2000s (five each).

It is fair to ask what the long-term legacy of the Moneyball A’s truly was. For all of its excitement, innovation and influence, the team that remained when Beane stepped back from day-to-day operations in 2022 had jettisoned most of its recent core and would sloppily initiate an ugly move to Las Vegas by way of Sacramento. The analytical age Beane had helped usher in — perfected elsewhere, from Tampa to Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles — was also widely blamed for detrimental changes to MLB’s quality of play,6 to the point that new rules needed to be adopted to combat those trends. The team still hasn’t won a championship since transitioning from a free-spending powerhouse to a penny-pinching, roster- churning machine.

When assessing the Moneyball A’s, though, one must concede that no team captured the spirit of early-2000s baseball quite like they did. Beane began molding this franchise at a moment of turbulence in the sport — a few years removed from the 1994 strike, a year away from the great HR chase of 1998 (and its subsequent steroid fallout) — and the rosters he built both reflected and accelerated trends that were already underway. The resulting teams were a perfect a fit for their moment — writing history that belonged in books, movies, spreadsheets… and eventually, legend.

CORRECTION (April 22, 2025, 10:10 a.m.): In an earlier version of this article — and the email version — the first chart listed the 2004 Boston Red Sox rather than the 2002 Oakland A’s. (I messed up when re-creating the chart format from this previous Team Timelines story.) It has since been fixed.

Filed under: Baseball, Team Timelines

And stayed with it continuously until the target team — so players who bounced back and forth from our franchise to others don’t count.

I’ll be using my WAR-based Win Shares for this, as they operate from a baseline of zero wins rather than negative values (like WAR), making them easier to deal with as percentages.

Who’d bought the team from the iconic Charley O. Finley in 1980.

That would be: Zito (19), Hudson (10) and Mulder (3).

Sans manager Art Howe, who famously did not see eye-to-eye with Beane — and was replaced by Ken Macha.

If not America at large!

Timeline leading up to the dynasty Yankees of 1996-200?

Why 2004 red sox for the chart?