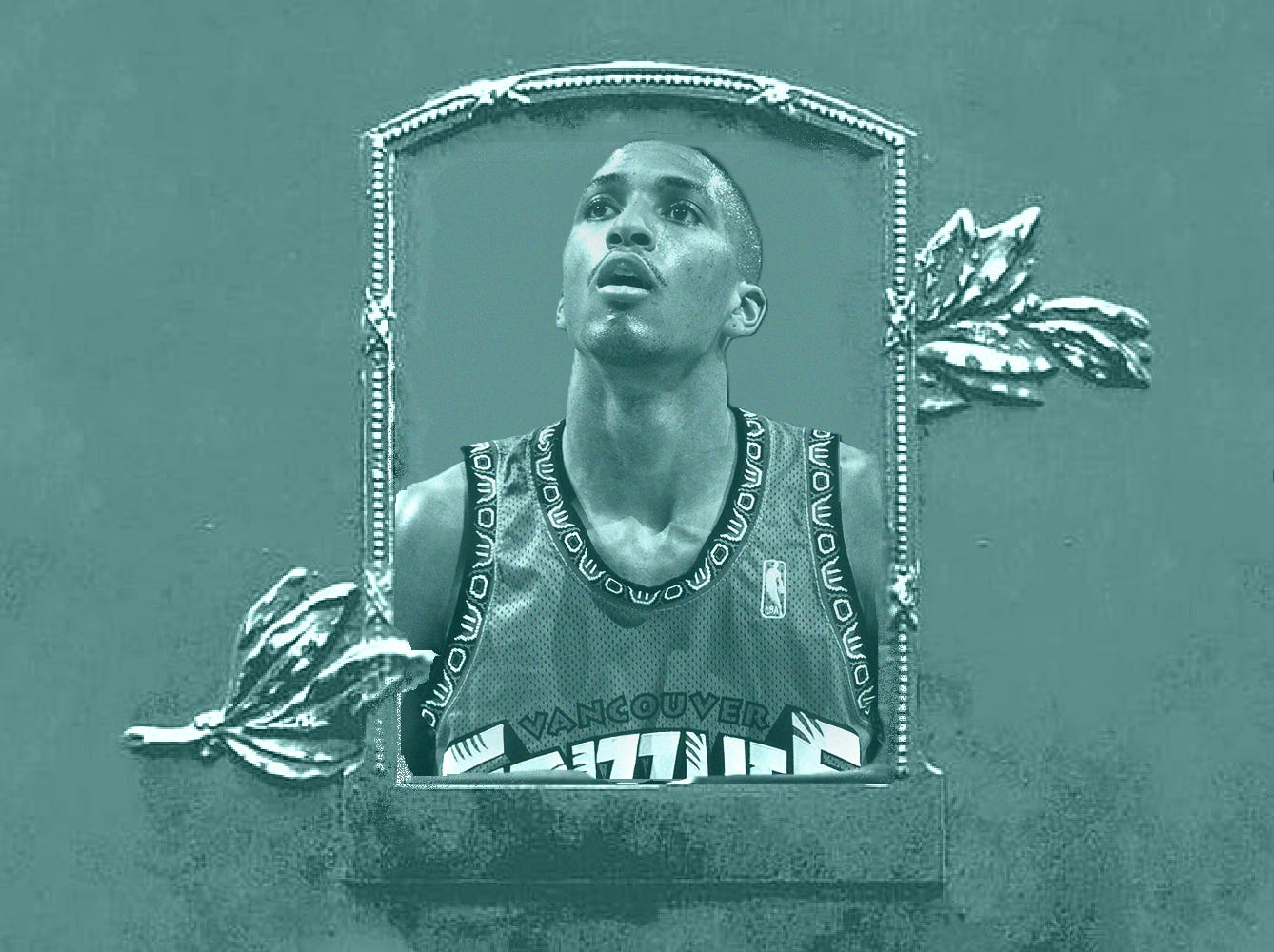

Shareef Abdur-Rahim Had Damn Good Stats on Some Bad Damn Teams

'Reef makes the Hall of Pretty Damn Good Players because he just kept putting up numbers — even though the wins never really followed.

Welcome to the Hall of Pretty Damn Good Players, our tribute to the overlooked athletes who haven’t gotten the respect they deserve over the years.

Recently, I’ve been realizing that the HoPDGP is quite short on basketball players, with Ben Wallace being the sole entry from the hardwood — and he made the real HOF since we originally wrote him up in April 2020. So today, I’m inducting a player that I loved growing up, but one who poses little threat to upgrade from the Hall of Pretty Damn Good to the Hall of Fame anytime soon: Shareef Abdur-Rahim.

The original “Shareef Abdur-Rahim All-Star”

I remember Shareef for a lot of reasons, but his lasting memory in the game today — aside from being drafted ahead of Kobe Bryant — might be as the archetypal player whose individual numbers never helped move the needle for his teams. Sure, he may have only made one All-Star Game, but Abdur-Rahim inspired an entire separate team of All-Stars, as coined by Bill Simmons during his ESPN era: the “Shareef Abdur-Rahim All-Stars,” also known as “guys best equipped to put up good stats for bad teams.”

So yes, he was the king of good stats on a bad team. But maybe that says just as much about his circumstances as it does about who he was as a player. Beyond just the numbers that were probably too often decried as empty calories, Abdur-Rahim was a lot more: A pioneer for Georgia hoopers, an iconic bright spot in a doomed expansion franchise, a guy drafted before legends — but hardly a bust. A player who performed well almost everywhere, yet won pretty much nowhere.

And a guy whose legacy in the sport is still tough to fairly pin down, even nearly two decades after he retired.

Georgia’s first NBA star in a generation

I was always drawn to Abdur-Rahim because, like me, he was a native Georgian — in his case, hailing from Marietta, a suburb northwest of Atlanta, in a family full of basketball-crazed brothers.1 It didn’t take very long for young Shareef to start drawing rave reviews for his play at local Wheeler High, where he was a two-time Georgia “Mr. Basketball” winner in 1994 and 1995.

Though he went west to UC Berkeley for one season of college ball, averaging 21.1 PPG for the Golden Bears in 1995-96, Abdur-Rahim was also the flag-bearer for Georgia basketball in the pros when he entered the draft. Before he began his NBA career in 1996-97, it had been more than a decade since any native Georgian2 who averaged at least 18.0 modified Points+Rebounds+Assists per game3 had debuted in the NBA, and nearly 30 years since the last Georgia product who was more productive by that measure than Shareef ended up being (Walt “Clyde” Frazier):

Needless to say, things look a lot different now. In the 2024-25 NBA, 21 players were born in Georgia and 23 went to high school there, a list that ranges from stars (such as Anthony Edwards and Jaylen Brown) to a bunch of good role players (like Kentavious Caldwell-Pope, Jae Crowder and Malcolm Brogdon) and plenty of others with potential. Other names certainly deserve credit for forming that pipeline, too — Dwight Howard might be the state’s best product, at least in the modern game — but Abdur-Rahim needs to be part of that story.

The 1996 draft problem

Immediately upon leaving Cal for the pros as an early one-and-done prototype, Abdur-Rahim was viewed as a franchise-changing talent — a versatile 6’9” scorer who could also rebound in the power forward role that was quickly growing in prestige. After dynamic Georgetown guard Allen Iverson and lanky, dominant UMass big man Marcus Camby went off the board, it was down to Shareef against the likes of Ray Allen, Stephon Marbury, Antoine Walker, Kerry Kittles — and maybe even a kid named “Kobe” — near the top of a loaded draft.

The Grizzlies went with Abdur-Rahim at No. 3.

In retrospect, no one really blames him for going before Marbury, much less ‘Toine or Peja Stojaković (who went later, at No. 14). But it’s admittedly rough to retroactively be expected to outperform future Hall of Famers Allen (No. 5), Kobe Bryant (No. 13) and Steve Nash (who was taken 15th).

Shareef ended up being in a very strange zone of draft legacy as a result. His solid career meant he could not be considered a bust by any means. Yet he was selected well ahead of multiple players who went on to become all-time greats. It’s something that unavoidably hangs over any assessment of his career, though it’s also not his fault that NBA general managers didn’t have the crystal ball to foresee who would develop into legends and who wouldn’t.

We also have no idea what Shareef’s career looks like if he goes to Milwaukee, Minnesota, Boston or anywhere else instead of Vancouver. Maybe he eventually becomes a second or third option on a playoff team — a role many pundits longed to see him in — rather than landing in basketball Siberia as a 19-year-old who was ready to produce big numbers, but not to carry a franchise to contention.

Grisly days in Vancouver

You work with what life gives you, though, and Abdur-Rahim found himself on a Canadian expansion team in only its second year of existence, coming off a 15-win debut season with its previous top draft pick (lumbering Bryant “Big Country” Reeves) already looking like a bust.

The early Vancouver years were simply weird as an NBA fit. This was a hockey city — the Canucks had just made the Stanley Cup final in 1994 — and pro basketball was trying to carve out its own niche without any pre-existing NBA infrastructure. As part of that branding effort, they wore turquoise, bronze, red and black colors that, while seen as oddly stylish (in a very ‘90s way) today, were unlike what fans were used to seeing, either locally or leaguewide.

Attendance in Vancouver wasn’t bad (17th out of 29 teams) in Abdur-Rahim’s rookie year, but it fell to 27th by the 1999-2000 season. It didn’t help that they kept whiffing in the draft, doing things like taking Antonio Daniels ahead of Tracy McGrady; Mike Bibby ahead of Vince Carter, Dirk Nowitzki and Paul Pierce;4 and trading Steve Francis for Michael Dickerson.

Against all of those chaotic factors, Shareef was good, delivering on his promise with a third-place Rookie of the Year finish in ‘96-97 and as an instant 22-and-7 guy at age 21 in ‘97-98. He gave legitimacy to a franchise that had none — and maybe even single-handedly made those original Grizz jerseys iconic.

A Hawks homecoming — and the Gasol what-if

At the same time, Abdur-Rahim’s hometown Hawks were in their own state of flux at the turn of the 2000s.

In an attempt to retool a core that kept losing to better teams — the Bulls twice, the Pacers twice, the Magic, Hornets and Knicks once apiece — in the playoffs throughout the ‘90s, Atlanta GM Pete Babcock dealt solid franchise anchor (and all-around good guy) Steve Smith to the Portland Trail Blazers for Jim Jackson and Isaiah Rider. The results were… um, not good. Ever the selfish head case, Rider became synonymous with a Hawks team that completely imploded in 1999-2000, effectively stopping one of the best eras of franchise history in its tracks.

After the failure of the Rider experiment caused them to miss the playoffs in back-to-back years, the Hawks were getting desperate to return in front of fans at shiny new Philips Arena. And Shareef’s tenure with the Grizzlies was going nowhere, too, as the team was contemplating a move from Vancouver to Memphis due to flagging attendance, a weak Canadian dollar and a chronic inability to surround Abdur-Rahim with talent.

Sensing a good match for both teams, Babcock pulled the trigger on a blockbuster deal to bring Abdur-Rahim back home, sending the Grizzlies the No. 3 pick in the next day’s NBA draft.

The only problem? That pick turned into Pau Gasol. And Pau had nearly five times as many Estimated RAPTOR Wins Above Replacement from 2001-02 onward (103.7) as Shareef did (22.7). Again, Abdur-Rahim quickly found himself living in the shadow of a move somebody else made to acquire him — setting up another comparison that he couldn’t win.

After the Hawks traded for him and shook up what little talent base they had, Shareef joined a weird mix of veterans (Toni Kukoč?) and young guys (Jason Terry) who made some improvements but still found it difficult to compete. The team went in again the following offseason, trading Kukoč and a first-rounder to the Bucks for Glenn Robinson — then guaranteeing the playoffs (or your money back!) — but the “Big Dog” was starting to be washed, and Atlanta failed to deliver on its playoff promise.

Abdur-Rahim would stick around for part of one more season in his hometown, but he was shipped to Portland when new GM Billy Knight cleaned house on the old regime. Shareef’s Hawks tenure would end with what became his hallmark: Impressive individual numbers (he averaged 20 and 9 with a positive RAPTOR each year) as a team imploded around him, in part because of a bad move that brought him there in the first place.

The most snakebit good player ever?

Amazingly, the Blazers would see a 21-year playoff streak (!) end the very season Shareef arrived, as the franchise’s “Jail Blazers” era was finally collapsing under its own dysfunctional weight.

It wouldn’t be until the 2005-06 season, in Sacramento at age 29, that Abdur-Rahim played his first career playoff series, a 6-game first-round exit at the hands of the San Antonio Spurs. While he was very solid that year (+1.1 RAPTOR), Shareef would decline sharply the following season, and transitioned to coaching early in the season after that.

Abdur-Rahim was barely into his 30s, and his NBA career was already over — finishing with just 6 career playoff games in the books.

For a player who, again, was actually pretty good, the stats on Abdur-Rahim’s lack of winning are mind-boggling. Among players with at least 40 WAR since the 1976 ABA merger, only Francis — his possible-but-not former teammate in Vancouver — played fewer total playoff games (5) than Abdur-Rahim’s mere six-game postseason stint:

Or consider Shareef’s lifetime on-court plus/minus rating of -5.4 points per 100 possessions. It is nearly unheard of for a player of Abdur-Rahim’s individual production to see his team be outscored by that much while on the court — either the player is bad, helping drag the team down, or the player is good and brings the team up. Abdur-Rahim is maybe the only player in modern NBA history who somehow doesn’t fit either of those categories: the only player with even 20 career WAR (much less 30 or 40) whose team had a -5 net rating or worse when he was in the game:

Maybe the top-line stats weren’t ever quite as good as they appeared. But Abdur-Rahim’s advanced metrics were hardly bad, either. It’s just that his teams were bad, despite his best efforts. In that way, you could build a case that he’s the ultimate “wrong place, wrong time” guy in NBA history.

A dying breed

Abdur-Rahim’s place in the hierarchy of ‘90s/2000s NBA icons wasn’t just hurt by his empty-stats reputation — his playing style has also left him without too many spiritual successors in today’s version of the game.

Certainly, Shareef was a silky-smooth player to watch in his highlights:

But think about the archetype he represented:

Midrange 6’9” post-up forward — good footwork! — with a high Usage Rate

Can face-up and put ball on the floor; runs the floor in transition

Could rebound, and maybe toss in a few stray blocks and assists

Not a floor-spacer, nor a good defender (-0.9 career Defensive RAPTOR)

That type of player has kind of faded out in the pace-and-space era. If we run his yearly percentile ratings through my similarity algorithm and look for the most comparable 2024-25 players to each qualified season of Abdur-Rahim’s career, here’s who we get:

1996-97: Jonathan Kuminga

1997-98: Trey Murphy III

1998-99: Trey Murphy III

1999-00: Deni Avdija

2000-01: Deni Avdija

2001-02: Deni Avdija

2002-03: Cameron Johnson

2003-04: Nikola Vučević

2004-05: Obi Toppin

2005-06: Deni Avdija

2006-07: Zaccharie Risacher

I like Deni Avdija as much as the next guy — he’s been the best player on a 2024-25 Blazers team that is surprisingly competitive lately — but I’m not sure I would have pegged him as taking on the mantle of “Next Shareef Abdur-Rahim” in the current NBA (nor really any of the guys on that list). That’s not to say this group is necessarily the most Shareef-like of all current NBA players in actuality, but more that it’s hard to find stars in today’s league with the exact statistical footprint that Abdur-Rahim left.

A Pretty Damn Good career… that could've been better

All of this makes for a fascinating career to assess in retrospect. The classic Simmons “Shareef All-Stars” label is clearly a swipe at the idea of certain players who pad stats in losing situations — though I think that undersells the actual Shareef Abdur-Rahim himself.

Yes, he put up superficially good stats on a bad team… but his advanced metrics were better than we knew at the time, too. (His True Shooting percentage was always above average, for instance, despite posting high Usage Rates.) He was on losing teams, but he didn’t play losing basketball.

He was also a multi-time victim of circumstance. You can’t blame him that Kobe and Pau ended up being far better than anyone imagined when they were drafted. He just had to deal with the rosters that were left in the aftermath.

The biggest knock on Abdur-Rahim was that he couldn’t elevate those teams to become something more anyway, and that’s a valid criticism for a No. 3 overall draft pick, even one who produced far more than any bust ever did. He would have been better suited to support a winning core than trying to lead one. It’s a shame we really never got to see that, especially not in his prime.

But if Shareef Abdur-Rahim was never quite great, he never had a real chance to be, either. Instead, all he had were the numbers on the stat sheet — and they were damn good.

Filed under: NBA, Hall of Good

One of those brothers, Amir, sadly died last fall, shortly before what would have been his second season coaching USF.

Defined as either being born in the state or attending HS there.

The “modification” is simply to weight rebounds and assists at 0.65 relative to points, in accordance with their relative weights in the Estimated RAPTOR formula.

This one was more excusable, as Bibby ended up having a long and productive career. Maybe he should get a Hall of Pretty Damn Good Players nod too?

Table 1 is fascinating! I figured Stevie Francis had made the playoffs more before he went to the Knicks (I figured wrong). I thought Gugliotta was a total NBA bust, but those are better numbers than I expected. And who is Alvin Robertson??? I consider myself a pretty big NBA fan and it's possible I've never heard that name before!