Optimizing the ’95 Rockets

Over in the comments of an earlier post about the 1990s Knicks, a discussion is raging about who the best player on the 1995 Houston Rockets was — Hakeem Olajuwon, or his old college teammate Clyde Drexler? At the core of the back-and-forth is whether Drexler’s 120.1 offensive rating (using 23.8% of Houston’s possessions when on the court) was more vital to the offense than Hakeem’s 109.8 ORtg (using 34.1% of possessions when in the game)… In other words, the old usage-efficiency debate. On one side, Drexler clearly contributed more points per possession to the Rockets’ effort than Olajuwon — but on the other side, Hakeem had to create offense on a significantly higher % of the Rockets’ possessions than Clyde, and if you subscribe to “skill curve” theory, this means Clyde’s ORtg was artificially enhanced by the extra defensive attention Hakeem drew — as well as the fact that his shot selection didn’t have to include the offense’s toughest shots, which were presumably going to Hakeem (at least in a larger proportion), in turn dragging down Hakeem’s ORtg.

We’ve been through all of this before at APBRmetrics, so this isn’t going to tread new ground or even settle the Hakeem-Drexler discussion, but here’s some more fuel to pour onto the fire…

In 2005, Dean Oliver (inventor of “skill curves”, at least in the way I discuss them here) ran a quick study that began to quantify the usage/efficiency trade-off at 0.6 pts/100 poss for each 1% increase/decrease in possession%. So the average player in 2005, with an ORtg of 106 on 20% possession usage, would drop to a 103 ORtg if forced to take on 25% possession usage. Another fascinating finding of Dean’s simple study was that the effect was amplified for low-usage players and diminished for high-usage ones. “If you run the regression on players averaging high or low use,” he wrote, “you see that the low use players (I used 18% as a cut off) are more sensitive to increases than high use players (23%). But both are still very significant. This implies that increasing Fred Hoiberg’s possessions 5% causes a bigger decline (about twice the size) than a similar increase in, say, Kevin Garnett. Or, from an optimization perspective, taking Garnett’s possessions (who increases in efficiency only a little) and giving them to Hoiberg (who declines in efficiency a lot) has a pretty big cost in even this crude analysis.”

That was a great starting point for me, and led me to develop what I called WARP (not to be confused with Kevin Pelton’s stat of the same name), which subbed a player for one with replacement-level production and tracked the difference in expected team wins, using Dean’s trade-off formula to measure the effects of swapping players on lineup efficiency. I suspected that the +/-0.6 tradeoff was not strong enough, as evidenced by mid-usage/high efficiency players like Jose Calderon ranking ahead of Kobe Bryant in WARP for a brief period during the 2008 season, but I went with Dean’s original study until something better came along.

That something came in March 2008, when Eli Witus conducted his own study on usage-efficiency tradeoffs using lineup data, which was a breakthrough because it eliminated many of the “chicken-and-egg” issues that had plagued earlier studies. Eli found in 2008, a league with an offensive rating of 107.5, that for each 1% a player increased his usage, his efficiency dropped by 1.25 points per 100 possessions.

For this post, I want to create a simple lineup efficiency model that combines Dean and Eli’s findings — specifically Eli’s tradeoff for average players (+/-1.25 in a 107.5 ORtg league), but Dean’s distinction between high-usage, mid-usage, and low-usage effects on personal efficiency (the effect on low-usage players is twice the effect on high-usage ones). What we in essence have, then, is a simple algebra problem: let x be the tradeoff for low-usage (<=18%) players and y the tradeoff for high-usage ones (>=23%). (x + y) / 2 = 1.25, and x = 2*y. What are x and y?

x = 1.6667, y = 0.8333

This means that in a 107.5-ORtg environment, the efficiency trade-off for increasing or decreasing usage by 1% is as follows:

We can also adjust each of these appropriately as a proportion of the league average when applying them to different environment (i.e., the tradeoffs would be .782/1.173/1.564 in 1978, when the league’s ORtg was 100.9).

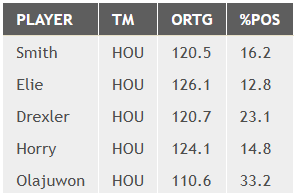

With information in mind, let’s look at the Rockets’ primary playoff lineup in 1995:

Those are their playoff-wide stats, and the Poss% don’t add up to exactly 100%, so we have to adjust the usages (and the efficiencies) accordingly. If we assume every player would take on 20% of the possessions, you get a team efficiency of 117.6:

Now, that’s obviously not how this lineup operated in real life; rather, the best guess is that they divided possession% up according to their playoff-wide rates, proportional to 100% total possession%:

That lineup yields an expected ORtg of 118.5, which is significantly better than the 117.6 we saw from the “perfectly fair” 20%-each lineup. But knowing the assumptions I laid out above regarding the various tradeoffs (and remembering that the league environment for the 1995 playoffs was 110.6 pts/100 poss.), can we further redistribute the possessions in this lineup to achieve an even higher offensive rating?

Actually, yes. The lineup above yields an offensive rating of 119.2, even higher than the “realistic” lineup that divvied up possessions according to playoff-wide Poss%. And if you optimize a lineup with Cassell at the point, you see similar results (actually, even better — a 120.3 ORtg):

Which means that, if you agree with the general ground rules I set at the beginning of this experiment, it’s not unreasonable to think the ’95 Rockets’ best strategy was to divert possessions away from Olajuwon and give more to Drexler, to the point that Drexler would actually be the highest-usage player in the lineup (and he’d still have a higher offensive rating). Let me be clear that I’m not saying Olajuwon wasn’t the better all-around player in those playoffs — he had a defensive rating of 107.6 and saved 0.77 pts/100 poss vs. the league average according to DPA; Drexler’s DRtg was 111.5 (worse than the league avg), and gave up 0.29 pts/100 more than avg by DPA.

So there’s a good chance Hakeem’s defensive edge offset Clyde’s edge on offense. But the take-home point is that Clyde did have an edge on offense, at least according to the skill curve assumptions I laid out, and that Houston may have been better off allocating more of Olajuwon’s possessions in Drexler’s direction. This is a highly simplified model of the game (as Dave Lewin said, “players often affect team efficiency differently than you might expect from their offensive rating and possession rate”), but as a very general rule it holds according to Dean and Eli’s studies, so at the very least these results can’t be dismissed out of hand.

Filed under: NBA, BB-Ref Blog, Statgeekery