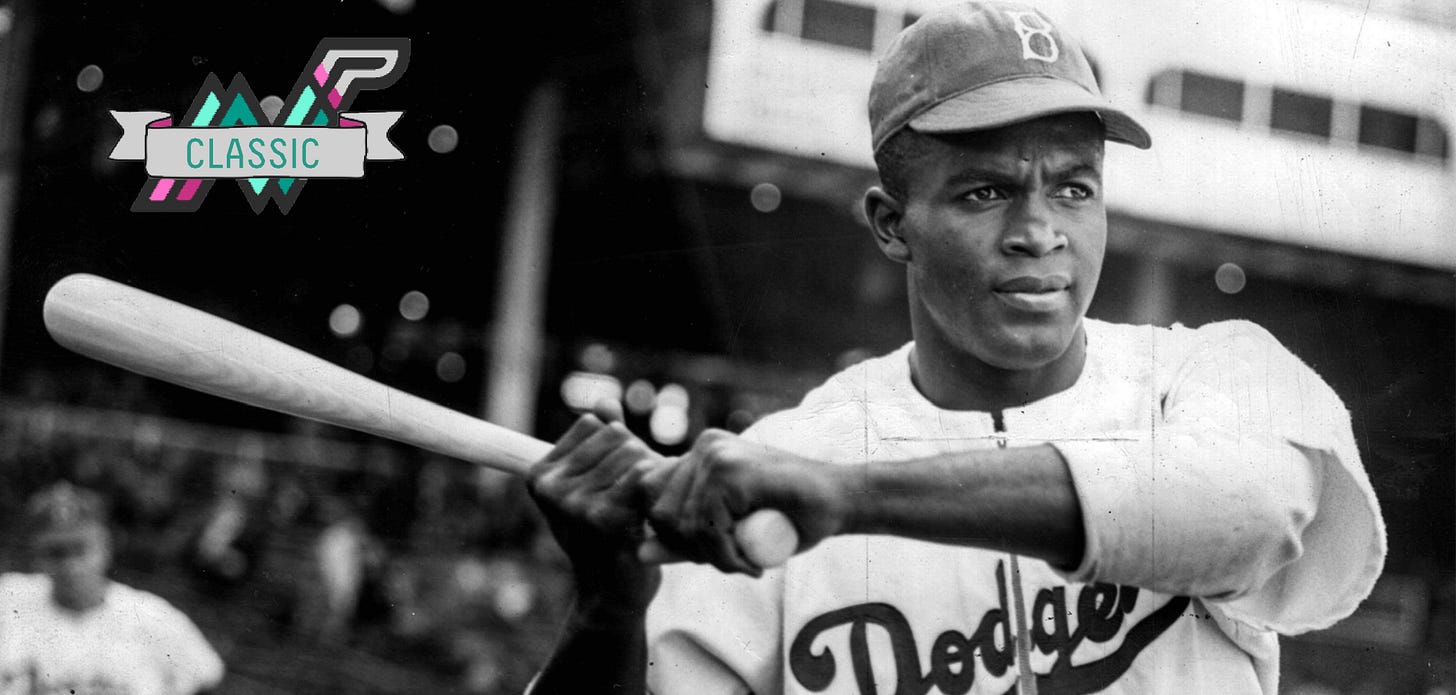

Classic Post: Jackie Robinson Was An Analytics Superstar

As baseball celebrates No. 42 again, the metrics still confirm his greatness.

Note: The following post is an updated version of a classic FiveThirtyEight post that ran in 2014.

On Tuesday, Major League Baseball will celebrate Jackie Robinson Day, honoring the 78th anniversary of Robinson eradicating baseball’s color barrier. The eponymous event, which fills baseball fields with the spectacle of countless players sporting No. 42, is a great reminder of Robinson’s legacy. It’s also a prime occasion to remind people that — despite his legendary small-ball artistry — yes, sabermetrics thinks he was an awe-inspiring ballplayer, too.

(It’s strange that anyone would need reminding — and yet, even in 2025, Robinson’s story isn’t always given its due. Thankfully, the numbers on his greatness still speak clearly.)

The topic recalls a great Rob Neyer post from more than a decade ago. Writing during the height of baseball’s culture wars (“Moneyball” had been published a month earlier), Neyer attacked the notion that sabermetrics wouldn’t have appreciated the skills of Robinson and other Black players whose contributions included steals — among other categories sometimes downplayed by the analytics. Notably, that group of stars contained Rickey Henderson, whose playing style and tremendous value made him, in many ways, Robinson’s spiritual descendant.

“You can accuse Bill James and sabermetrics of many things, but you cannot accuse them of not appreciating Jackie Robinson and Rickey Henderson,” Neyer wrote. “Those two brilliant players — not to mention Joe Morgan and Willie Mays and Cool Papa Bell and Barry Bonds, and hey let’s not forget Henry Aaron and Frank Robinson and Tony Gwynn and Eddie Murray — could play for any general manager.

“If you think that sabermetrics doesn’t have a place for them,” he continued, “then you don’t understand sabermetrics. Because there’s not yet been a sabermetrician born who wouldn’t drool at the thought of Rickey Henderson and Jackie Robinson at the top of his imaginary lineup.”

Yes, Robinson ranks just 103rd all-time among position players in lifetime Wins Above Replacement at Baseball-Reference, and 128th at FanGraphs. But that’s a function of the late start he got to his AL/NL career (he was a rookie at age 28) and his relatively short playing stint — even after MLB began recognizing statistics from the Negro Leagues in 2024. (Because of his duty to our country, serving in the U.S. Army, Robinson missed the 1942-44 seasons, wiping out years when he would have been ages 23-25.)

Once he finally tore down the color line and made his National League debut, Robinson was immediately a big-time star. After ranking 12th in 1947, he was the NL’s seventh-best position player by WAR1 in 1948, his second season, then led the senior circuit in the statistic in 1949, 1951 and 1952, while also finishing second in 1950 and fifth in 1953. This shouldn’t have been a surprise; as I wrote here in a story about Kim Ng, the first female GM of a “Big Four” men’s league team:

Think of an earlier baseball trailblazer, Jackie Robinson, who instantly played like an MVP after breaking the color barrier — representing the tip of an iceberg of great Black players who had been unjustly denied entry to MLB. Or how Black NFL quarterbacks still tend to be better than their white counterparts, decades after Doug Williams and Warren Moon: Going into Week 10, the average Black starting QB this season carried an Elo rating 24 percent better than the average white QB. This is simply a selection effect at work: People who tear down barriers of prejudice have to be that much better in order to reach the same level of status as those who don’t face discrimination.

By 1954, Robinson was 36 and his quickness was on the wane (that year he posted a career-low speed score of 4.6 with -0.3 baserunning runs above average, the only time he was ever below the league average in either stat). He would retire after two more seasons. But that 1948-53 peak was just about as good as anybody’s ever been. Literally. Only seven other position players in MLB history — Willie Mays, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Lou Gehrig, Joe Morgan, Mike Schmidt and Hank Aaron — had more WAR between the ages of 29 and 34. Numbers like that are why, despite Robinson’s short career, James ranked Robinson as the fourth-best second baseman ever in “New Historical Baseball Abstract.”

So much for analytics underappreciating Robinson’s skills.

WAR can measure Robinson’s terrifying impact on the basepaths (he generated 35 more runs than an average player). WAR also takes into account his defensive value — my aggregate of Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs data estimates that Robinson saved 82 more runs than an average defender (primarily at second base, but with a little third base, first base and outfield mixed in). Add in the positional value of where he played, and Robinson saved the Brooklyn Dodgers 100.3 runs (or about 10 total wins) with his defense overall, a number that rates him among the best second basemen with the glove to ever play the game.

Most importantly, though, WAR accounts for the fact that Robinson was 274 runs better than average with his bat. Because of the highlight-reel baserunning plays, people often forget that Robinson was also an incredible hitter. He topped a .295 batting average eight times, winning the NL batting crown in 1949 with a .342 average. He also had the majors’ seventh-highest on-base percentage during the course of his career (1947-56), drawing a walk on 12.8 percent of his plate appearances in addition to his outstanding ability to hit for average. And his isolated power was 19 points better than the league average, so Robinson had some pop (even if his slugging percentage was driven in part by 54 career triples).

In sum, Robinson was an all-around analytics star. There isn’t an area of the game where the advanced stats don’t consider him very good, if not one of the best ever. The notion that somehow Robinson has lost his luster as we learn more about what makes for winning baseball couldn’t be further from the truth.

If anything, sabermetric stats help us appreciate Robinson’s greatness even more. And while his legacy should be above politics, it remains as vital as ever to reassert just how extraordinary he was, both on and off the field.

Filed under: Baseball

Using my JEFFBAGWELL metric to blend WAR from Baseball-Reference.com and FanGraphs.