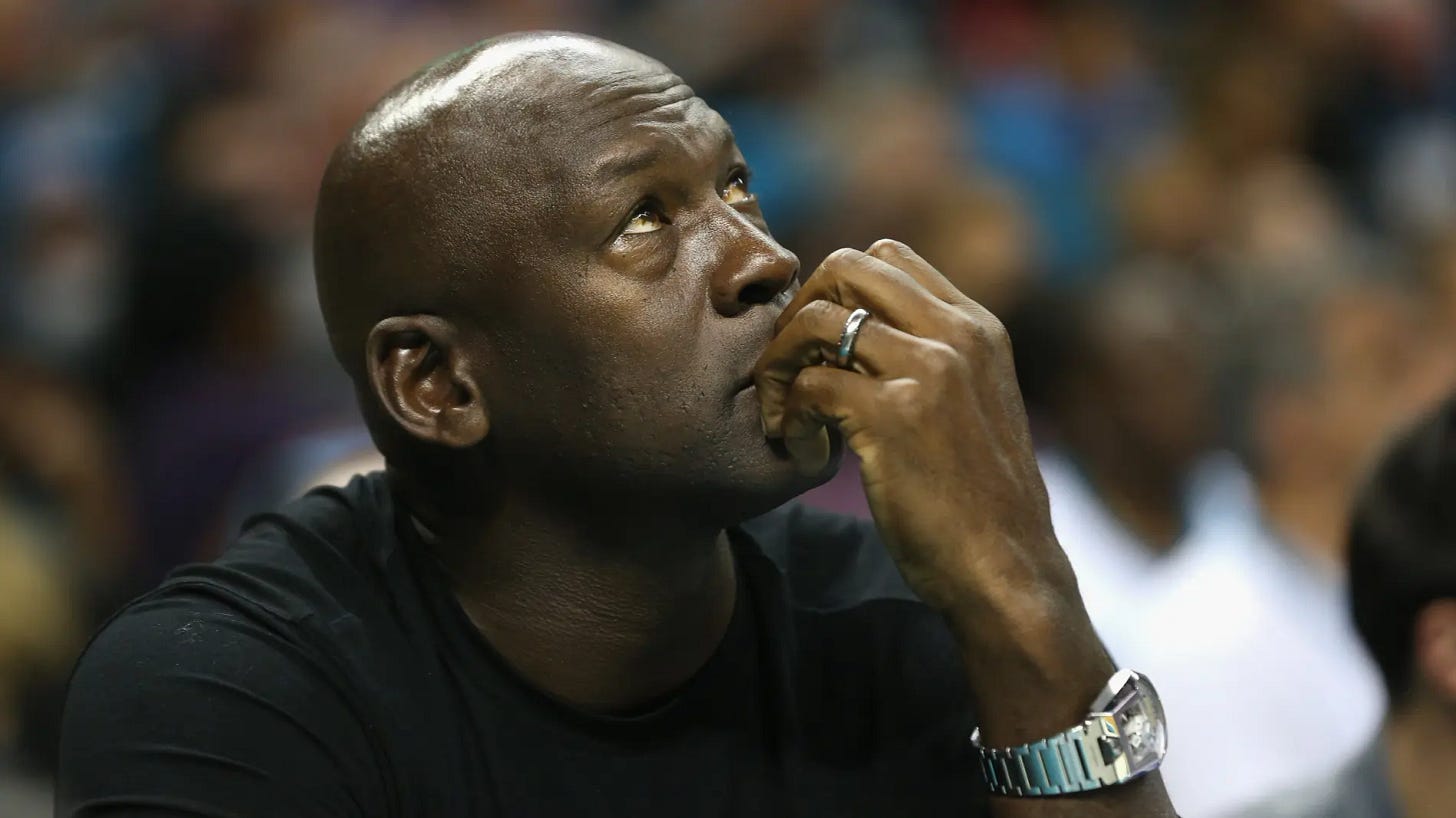

Where Did Michael Jordan’s Hornets Tenure Go Wrong?

Basketball’s most obsessive winner was one of its biggest losers in Charlotte.

Although the approval of Michael Jordan's sale of the Charlotte Hornets by the NBA's Board of Governors this week was expected — he had agreed to sell his majority stake in the team last month — it still marked the end of an era. Nearly two decades ago, the greatest player in NBA history came home and took over his local NBA franchise (then known as the Bobcats), first as a co-owner and then as the outright boss. The league’s most maniacal winner during his days on the court, Jordan described team ownership as the ultimate goal for his retirement years.

"Purchasing the Bobcats is the culmination of my post-playing career goal of becoming the majority owner of an NBA franchise," Jordan said at the time. "I am especially pleased to have the opportunity to build a winning team in my home state of North Carolina. I plan to make this franchise an organization that Charlotte can be proud of.”

But MJ’s tenure running the Bobcats/Hornets was far from the success he prescribed. During his run of majority ownership alone, Jordan’s team piled up 600 losses; overall, it went 567-784 during his entire connection with the franchise — good for the league’s fifth-worst record — while making the playoffs only three times (with just three wins) in 17 seasons. How did the NBA’s greatest competitor as a player end up losing so much as an executive?

Skeptics of Jordan’s Charlotte stewardship could look back to his days with the Washington Wizards for clues about what might be to come. While MJ’s stint with the Wizards as a player might fairly be called underrated (I did a deep dive on that here), his time in D.C. as an exec was more questionable. As part-owner and president of basketball operations, Jordan oversaw the infamous pick of Kwame Brown with the No. 1 selection in the 2001 draft, part of a collection of picks that — if we also assume Jordan had some sway over the 2002 draft, despite actively playing at the time — collectively undershot their expected career value by 116.7 Win Shares, without a single player achieving the potential indicated by his pick slot. He also greenlit the trade of 24-year-old future All-Star Rip Hamilton for 28-year-old former All-Star Jerry Stackhouse.

Nevertheless, Jordan became Charlotte’s part-owner and manager of basketball operations in June 2006. He inherited a recent expansion team that ranked dead last in payroll and had gone 44-120 in its first two seasons of existence, but one which also had some interesting young players (such as 23-year-old forwards Gerald Wallace and Emeka Okafor, and 21-year-old point guard Raymond Felton) plus the No. 3 pick in that summer’s draft. Of course, the team promptly spent that pick on Gonzaga’s Adam Morrison — who ended up joining Brown on the NBA’s list of all-time draft busts — and the tone was set for MJ’s regime early.

There were, however, glimmers of hope at various moments. Building around Wallace, Felton, Boris Diaw and Stephen Jackson, the Bobcats went 44-38 under coach Larry Brown in the 2009-10 season to earn Jordan the first playoff appearance of his post-playing career. Though Charlotte was swept in the first round, Jordan had been stacking positive offseasons on top of each other for a few years. Observers at the time thought maybe the team could build on that success.

Instead, calamity ensued. The 2010-11 Bobcats regressed and Brown left the team in classic Larry Brown fashion. The players who had powered the playoff run a year earlier got worse. Jordan’s personnel shuffling was a mess. And it all set the stage for 2011-12, which gave MJ plenty to cry about as Charlotte endured one of the most miserable seasons in the history of team sports.

After recording the worst winning percentage by any NBA team ever, Charlotte didn’t even get the No. 1 overall pick in the following draft. Instead, the lottery bounces sent the first choice to the New Orleans Hornets (which, confusingly, later became the New Orleans Pelicans, transferring the “Hornets” name back to Charlotte). New Orleans would select franchise-altering Kentucky big man Anthony Davis. Charlotte was relegated to taking his less talented teammate Michael Kidd-Gilchrist, who currently has nearly six times fewer career Wins Above Replacement than Davis — and roughly four times fewer WAR than No. 3 pick Bradley Beal, for that matter. (No. 6 pick Damian Lillard has the most career value from anyone in that draft, generating 6.3 times more WAR than Kidd-Gilchrist.)

Such a combination of bad luck and poor decision-making was common throughout Jordan’s time in Charlotte. Including the case of Davis and Kidd-Gilchrist, four different drafts saw Charlotte miss out on a player in the lottery who ended up producing at least 25 career WAR, getting a consolation prize who generated significantly less with the following pick. But lest we feel too sorry for Jordan’s lousy luck, there were also nine instances in 15 lottery picks where the player taken directly after Charlotte’s pick had more value than the player Charlotte ended up taking — something that probably shouldn’t happen more than half of the time when you have the better pick.

This means that if you plot out the future WAR for Charlotte and its surrounding picks under Jordan, there’s a “dip” in the graph when it comes to the team’s chance at picking — it got less value than either the team that picked before it or after it, on average.

The soon-to-be-Hornets did climb back above .500 within a few years of the catastrophe that was the 2011-12 season, thanks to the improvement of former No. 9 overall pick Kemba Walker (probably the best draft choice Jordan ever made) and the additions of competent veterans such as Al Jefferson. While that was, once again, only good enough to get Charlotte swept in the first round — this time by LeBron James and the defending-champion Miami Heat — there was renewed hope that the franchise was finally on the right track, accentuated by the long-awaited return of its Hornets branding.

That momentum stalled a bit when Charlotte dropped back below .500 and out of the playoffs in 2014-15 — a season that included the disastrous Lance Stephenson experiment — but the team bounced back to set a new post-Bobcats-era (i.e., excluding the original Hornets) record with 48 wins in 2015-16. Walker improved to set a career high for WAR; the team’s newcomers, as led by Nic Batum, played well; and Charlotte even held a 3-2 lead over the Heat in the first round of the playoffs… before losing back-to-back games to be eliminated. (Walker had 37 points in Game 6 but fizzled to 9 points in Game 7.)

Nobody knew it at the time, but that would be Charlotte’s final playoff appearance under Jordan’s ownership — and, presumably, Jordan’s last taste of the postseason leading any team. The Hornets won between 33 and 39 games in four of the next five seasons, the exception being a 23-42 record in the pandemic-shortened 2019-20 campaign. And while they won 43 games with Miles Bridges, Terry Rozier and LaMelo Ball leading the way in 2021-22, they were quickly ousted by Atlanta in the play-in tournament. Then they fell to 27 wins last season, as Bridges missed the entire year after pleading no contest to a felony domestic violence charge, while Rozier’s performance tanked and Ball suffered a fractured ankle.

Thus, the Jordan era ended not with a bang, but with a whimper.

So what were the big takeaways from Jordan’s stewardship of his home-state franchise? One certainly was that MJ didn’t have the same ability to elevate a team from the front office that he did as a player. There are counter-examples of former great players who became great executives — Larry Bird and Jerry West were nearly on Jordan’s level as players, and both proved to be shrewd talent evaluators as well (West in particular might well be the best GM in NBA history) — but Jordan has spent two decades proving he could never join that club.

We might be tempted to think Jordan used his own greatness as a reference point, spending too much time and energy pursuing players who fit a similar archetype to himself. But in reality, very few of Jordan’s top draft picks were built like or remotely played like His Airness. Maybe the closest in terms of big, scoring guards were Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and LaMelo Ball, but neither is the defender MJ was (and Jordan shipped Gilgeous-Alexander away at the 2018 draft anyway). More often, Jordan spent his draft capital on traditional point guards and big men, with checkered results at best.

Another factor limiting Jordan’s success in Charlotte was the team’s inability to snag premium free agents. In terms of single-season WAR, the highest-impact free agent Charlotte added during the Jordan era was (by far) Jefferson in 2013-14. Absent better options than that, the team was stuck overpaying the max for Gordon Hayward, giving Batum far too much money to stick around or trafficking in lower-tier additions like Rozier or Kelly Oubre Jr. None of that was truly going to move the needle for Charlotte’s championship odds, which might explain why the team stayed on the dreaded “Treadmill of Mediocrity” for so long.

Along similar lines, the Bobcats/Hornets usually carried a payroll that ranked among the NBA’s lowest under Jordan’s watch. Although the relationship between spending and winning in the NBA is different from an uncapped league like MLB, Charlotte ranked among the top half of teams in payroll just four times in MJ’s 17 years running the franchise, the same number of times it ranked among the bottom three. Whether by choice or the constraints of the NBA’s financial system, Jordan didn’t spend a ton of his own money on his team over the years.

All of this was further hamstrung by a lack of creative solutions to get production from unexpected places. Perhaps the only three non-lottery picks by Charlotte who went on to have good NBA careers — Tobias Harris, Jared Dudley and Dwight Powell — were all traded away very early. (Harris and Powell didn’t even make it past draft day, while Dudley was dealt midway through his second season.)

Because of the challenges facing Charlotte as one of the NBA’s smallest markets, the margin for error was always going to be narrower for Jordan than for other teams’ bosses. As such, expecting MJ to replicate a Chicago Bulls-style dynasty in his home state would probably have been unrealistic. However, it bears noting that the San Antonio Spurs formed a dynasty out of an even smaller market during roughly the same span of years.

In the end, the things that made Jordan the GOAT as a player — his competitiveness, efficiency and relentless drive to improve both himself and others — simply didn’t translate to being a successful owner and executive. While MJ’s legacy as an NBA legend can never be tarnished, his post-playing career is a reminder that greatness always has its limits.