Denny Hamlin Is NASCAR's Best Driver Without A Title. That Could Change Soon.

The win would be fitting in a messy, imperfect season — for both driver and sport.

Even by the standards of a career filled with beefs, Denny Hamlin’s 2022 season has been particularly drama-filled. He’s feuded with multiple drivers, was ordered to undergo sensitivity training in April for retweeting a racist meme, became the first racer since 1960 to have a win taken away during a post-race inspection in July and, more recently, has been among NASCAR’s most outspoken critics over the new next-gen car’s safety concerns — outright calling for the sport to have “new leadership” earlier this month. Nearly 20 years into his Cup Series career, Hamlin has shifted his prickly persona and knack for making enemies (which he admits hurts his popularity among fans) into high gear.

It hasn’t been the smoothest of seasons on the track, either. Though he has a pair of wins on the year,1 Hamlin’s average finish of 16.7 is the worst he’s posted since his miserable 2013 campaign, and his 12 top 10s ranks last among Joe Gibbs Racing team drivers — several of whom have endured down years of their own. Yet, Hamlin’s performances have steadily improved as the season has progressed, and a well-timed string of five top 10s (and three top fives) in six playoff races has put him in a position to potentially win his first-ever Cup Series championship. According to the futures odds, only 2020 champ (and 2022 regular-season point leader) Chase Elliott has better odds to win than Hamlin as the series shifts to Las Vegas, where Hamlin happens to be the defending race winner, for the Round of 8.

And if Hamlin does win, his title would carry surprising historical significance. Just like golf has its Best Player To Never Win A Major, NASCAR has its best drivers who never won a Cup Series title — and you can make a strong case that Hamlin is racing’s version of that guy… for now.

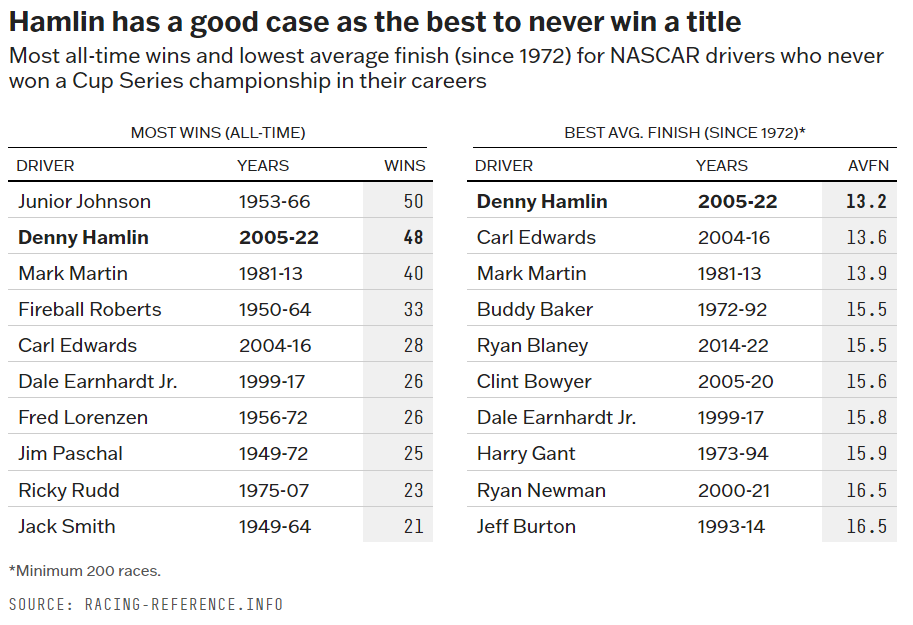

Starting with the most basic of measures, Hamlin’s 48 career Cup Series wins are tied for 16th all-time, ranking second among non-champions behind Junior Johnson’s 50. Johnson, who was perhaps better known later on as a team owner/pork-product salesman, was a folk hero driving in NASCAR’s earliest era. But aside from raw wins, Hamlin drives circles around Johnson’s record in terms of top-five (206 versus 121) and top-10 finishes (317 versus 148), and has him beat on average finish as well (13.2 versus 13.5). Besides, Johnson ran his entire career before 1972, when the Cup Series’s modern era truly began.2 Among non-champions with at least 200 career races in the modern era, Hamlin beats out Carl Edwards for the best average finish of any driver.

There are plenty of other strong candidates among the best to never win a title, to be sure. Another “Junior” — Dale Earnhardt, Jr. — famously never won a championship despite embodying the heart and soul of the sport better than anybody else in the wake of his father’s untimely death. Edwards, who ended his career as a JGR teammate of Hamlin’s, backflipped his way to nearly 30 wins while just (and I mean just) missing out on a couple of titles. And Mark Martin has long been the default leader in NASCAR’s always-a-bridesmaid rankings, finishing second in the standings five times and third on four other occasions.

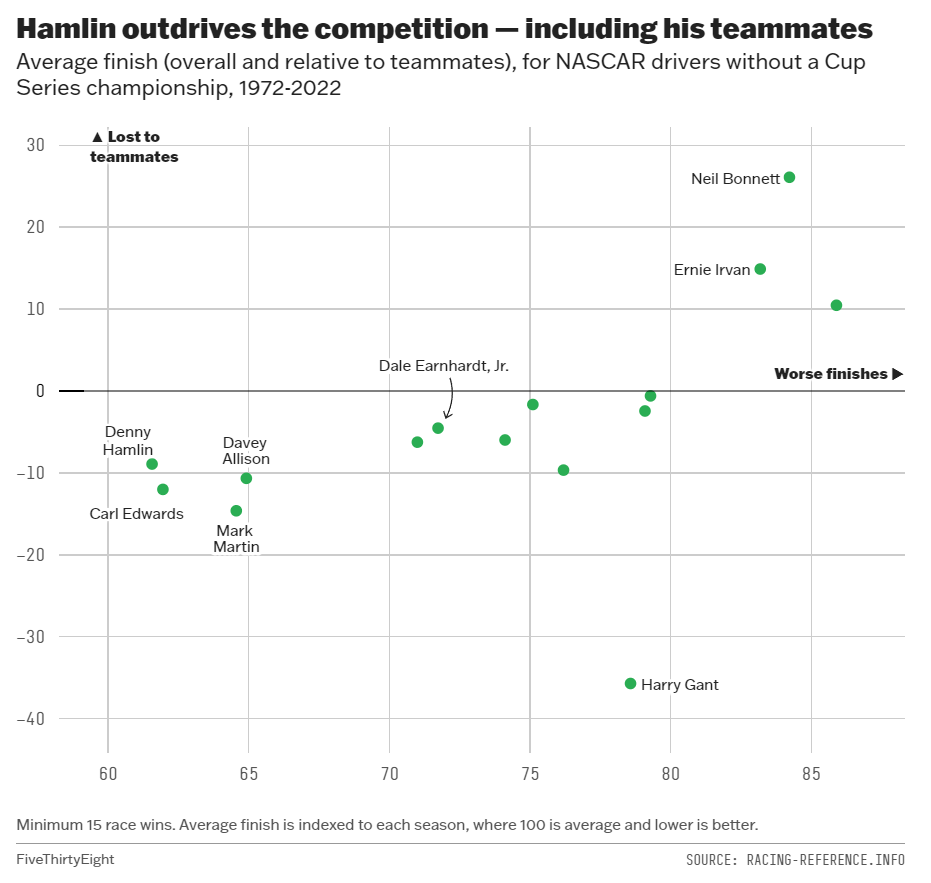

Because a driver’s record is so tied up in the quality of his car, crew chief and other team factors, it’s difficult to say for certain whether Hamlin is better than his winless rivals. (It’s also a mantle no driver would really fight for anyway, if they had a choice.) But we can do a little work to compare each driver with both the field and their teammates. I indexed average-finish data from Racing-Reference.info against the NASCAR Cup Series average each season, in the manner of FanGraphs’ “minus” stats for baseball pitchers — where 100 is average and lower is better. Hamlin’s career Finish- of 62 means his typical finish was 38 percent better than the average driver, which is tied for sixth-best among all drivers with at least 200 races since 1972. I also computed the average Finish- of driver’s teammates in the same season to get a baseline expectation for drivers with similar equipment. And while Hamlin has always driven for a good team at JGR, he’s managed to beat his talented colleagues by 9 points of Finish- on average.

Though that number lags Martin (who had a 65 Finish- but beat teammates by 15 points) and Edwards (62 and 12), it handily beats Earnhardt Jr. (72 and 5) and ranks among the best of the non-champs. (Notwithstanding the incredible outlier that was Harry “The Bandit” Gant, who switched teams often in the 1970s and ‘80s but always dominated whoever else drove those cars.) All told, Hamlin’s combination of absolute and relative performance makes him as good a pick as any for the best driver without a Cup title.

There’s a certain measure of irony that 2022 could be the season to remove that tag from Hamlin’s career. He’s had other, far more dominant performances over the years — including 2009, when he finished fifth but beat JGR teammates Kyle Busch and Joey Logano by 22 points of Finish-; 2010, when he led the standings going into the final race but lost the championship to Jimmie Johnson; and one of 2019, 2020 or 2021 (take your pick), when Hamlin lost in the Championship 4 three straight years despite notching the best Finish- (46), most wins (15) and most top-five finishes (56) of any driver. Compared with those performances, Hamlin’s 2022 numbers — an 88 Finish-, two wins and eight top fives in 32 races — seem downright pedestrian. But the upward trajectory of his season, combined with the quirks of NASCAR’s playoff system and the lack of a dominant alternative in the next-gen car’s debut campaign, makes Hamlin’s first career championship a very real possibility.

It might also be Hamlin’s last good chance to remove himself from the best-to-never-win club. At age 41, he is hitting the career phase when a driver’s performance tends to fall off a cliff; Hamlin even talked about that research in a conversation with Earnhardt earlier this year. His future as a team owner — not a driver — is beckoning, as the 23XI Racing team he founded with Michael Jordan in 2020 has expanded its roster of up-and-coming drivers to include Bubba Wallace and, soon, Tyler Reddick. (In classic Hamlin-esque fashion, Reddick’s departure from Richard Childress Racing couldn’t be tension-free.) So if there was ever a time for Hamlin to finally add a championship to his resume, it’s this season — as messy, drama-filled and imperfect as it has been.

Filed under: NASCAR

Not including the stripped win at Pocono in July.

RIP Mark Martin. He's in danger of losing the only crown I thought he would never lose.

I love how you categorize performance both relative to the field and relative to one's own teammates, because I think the perception that swings this argument oftentimes is that the Roush cars were always really weak (with the exception of about 2002-13, but that misses Mark's prime) and the Gibbs cars were always really strong, especially upon the Toyota switch. This is the weird thing about auto racing, as points are scored relative to the field, but driver evaluation is often done relative to one's teammates.

In all honesty, I thought Mark would be much further ahead than this. Pour one out for Harry Gant. I don't know what the story behind that teammate domination is all about, but he's just too far behind in performance relative to the field to be a part of this discussion, which leaves us with the quartet in the bottom left quadrant of Hamlin, Edwards, Martin, and Davey Allison.

Considering you used the word best (and not greatest), Davey Allison gets to stay despite the very short career he had, but the issue is that the meaning of the word championship is different for all of these four men. Championship in Davey's day meant the best and most consistent driver over the course of a whole season, in a system that rewarded not being bad much more than it rewarded being good, which is where Davey struggled. Just one fewer DNF in 1992 and that championship could've been his easily, despite being well off top form for most of the season.

Mark's style was perfectly tailored to this system, but he just got the horrendous luck of having to share his best years with the monstrous Hendrick 24 car. As soon as Jeff started falling off with the departure of Ray Evernham, Mark had started falling off also. Mark's 1998 would've been a championship in almost every other season. If he could've had his 1998 not in 1998 he wouldn't have been on this list either.

For Carl, the definition of championship had changed to the best driver over the final ten races of the season, which was not quite Carl's style. He still very nearly did it in a Roush car that just didn't have the speed in 2011 (if it did he would've won more than once), but fell just short in an effort that remains extremely impressive even in the absence of a championship.

For Denny, the championship is not about being the best at all. He did get near one championship in the original chase era, but for the most part his true contending has been done with the elimination format, which can't decide what it wants to reward. It doesn't reward winning (if it did, why do two and three win drivers keep winning championships?). It doesn't reward consistently finishing well either, because regular season rewards are not big enough, and the gap that can be built in three weeks is not big enough.

These days, championship four appearances almost mean more than the championships, which comes close to disqualifying Denny from being in this argument at all for me.

That comment turned out to be very long, but in short, I'm not sure of the answer to the question 'the best driver without a championship,' and I'm not sure if I ever will be, because what a championship is and what it means across this main quartet changed two different times, from being the best team and driver over the whole season, to being the best driver and team only across the final ten races, to ... whatever we have now. These drivers and teams were chasing entirely different goals, so it almost doesn't feel right to compare them.