Collapse of Red Sox Offers Stark Lesson in Team Chemistry

Give some credit to the Red Sox — they have not been kept out of the postseason after all.

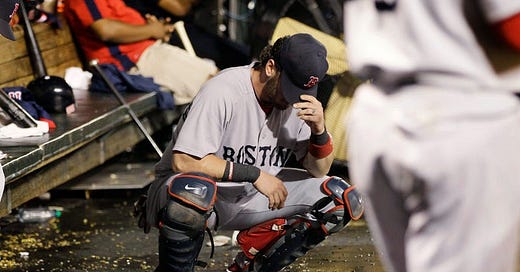

While four superior teams have been battling on the field for World Series berths, Boston’s historic late-season collapse continues to make news, with substantial allegations that as the season progressed, a culture of unprofessionalism took hold under Manager Terry Francona, who left at the end of last month.

Perhaps the most damaging assertion is that several starting pitchers were sneaking off to the clubhouse for beer, fried chicken and video games while their teammates were on the field.

If you could quantify Boston’s chemistry for the 2011 season, it probably would be revealed as the worst in baseball. But therein lies a major problem for objective baseball analysts: team chemistry, as perhaps baseball’s most beloved intangible, defies all measurement. As a result, it has always been a nearly impossible puzzle for sabermetricians to solve.

In an endless series of one-on-one matchups between the batter and the pitcher, the interactions between teammates are minimal enough that sabermetricians can usually pretend they do not matter. Still, there is plenty of research to suggest that the Red Sox were not helped by the problems laid out in recent news reports, including a front-page article in The Boston Globe that described a lack of leadership, unity and commitment to conditioning.

When studying the cohesiveness of groups like military units, psychologists make a distinction between social cohesion and task cohesion.

Social cohesion refers to the bonds among group members, or what we would think of as the camaraderie among teammates in sports.

Task cohesion refers to the commitment and responsibility each member shares in achieving a common goal.

Most talk of chemistry in sports focuses on social cohesion, but studies have found that task cohesion is what affects a group’s success.

For example, it is not essential that Jacoby Ellsbury and Kevin Youkilis be friends, but the fact that Josh Beckett, John Lackey and Jon Lester may not have been fully committed to conditioning would have had a negative impact on the team beyond the damage done by their poor pitching.

From a sabermetric standpoint, this kind of human element is often seen as a confounding factor, a messy variable that cannot be accounted for (and often does not need to be). But the evolution of analytics may lead to the capacity to embrace the chemistry problem and turn it into a competitive advantage.

In professional basketball, companies study player personality types to determine the best fit for a team beyond X’s and O’s. Using souped-up versions of the classic Myers-Briggs questionnaire, the tests they administer break down a player’s mental makeup in categories ranging from coachability to team identity. This information can help decision makers know the type of environment in which the player is built to succeed — or destined to fail.

In the future, this kind of analysis may even be able to identify questionable clubhouse personalities, or problematic combinations between teammates, before major financial commitments are made.

Filed under: Baseball, Classic Posts